Summary part 2:

- Big data requirements and external changes require frequent adjustments to in-system storage and processing solutions.

- The transition to new database and event streaming technologies is facilitated by query languages that refer to a common standard such as “ANSI SQL”.

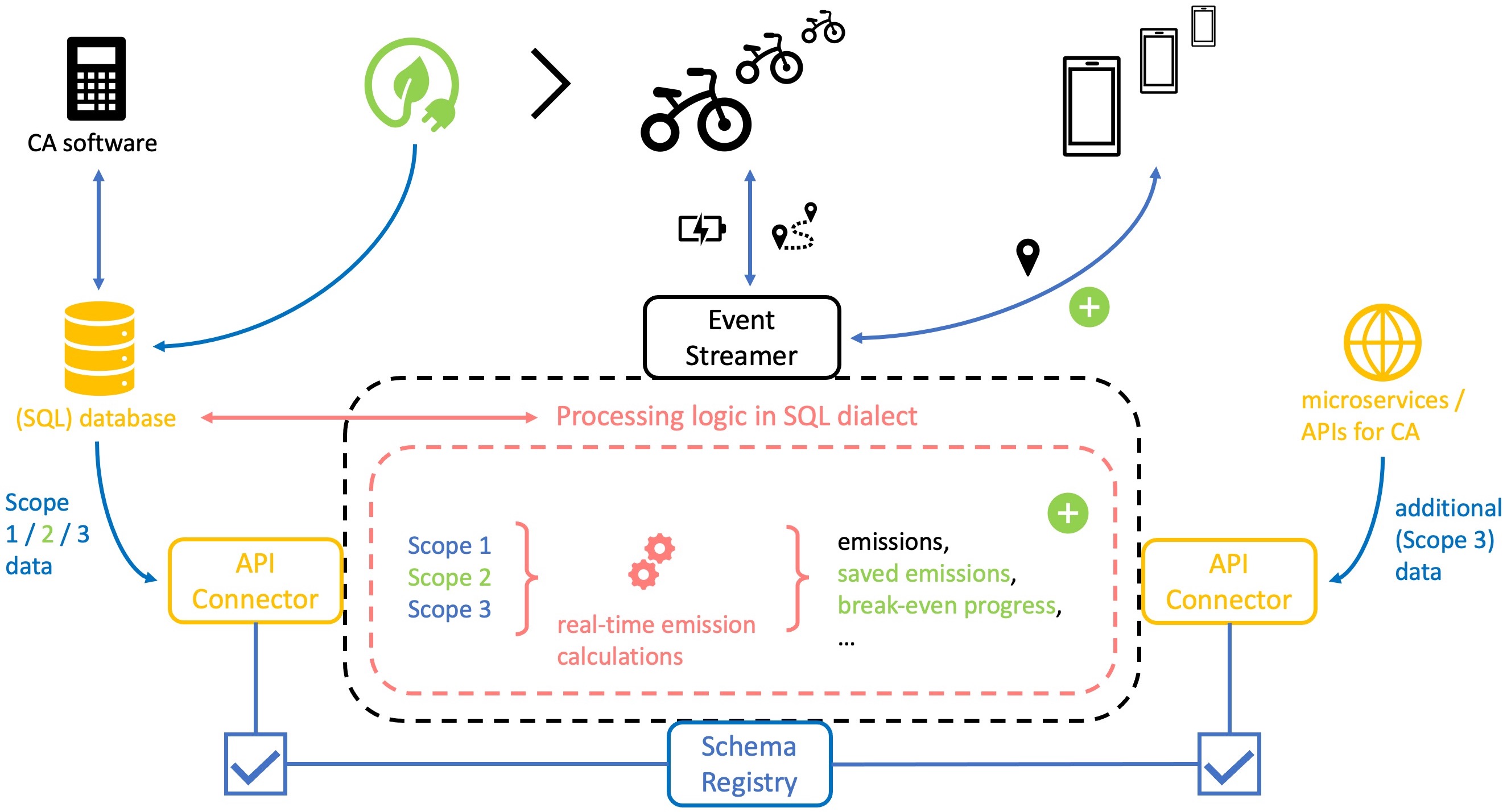

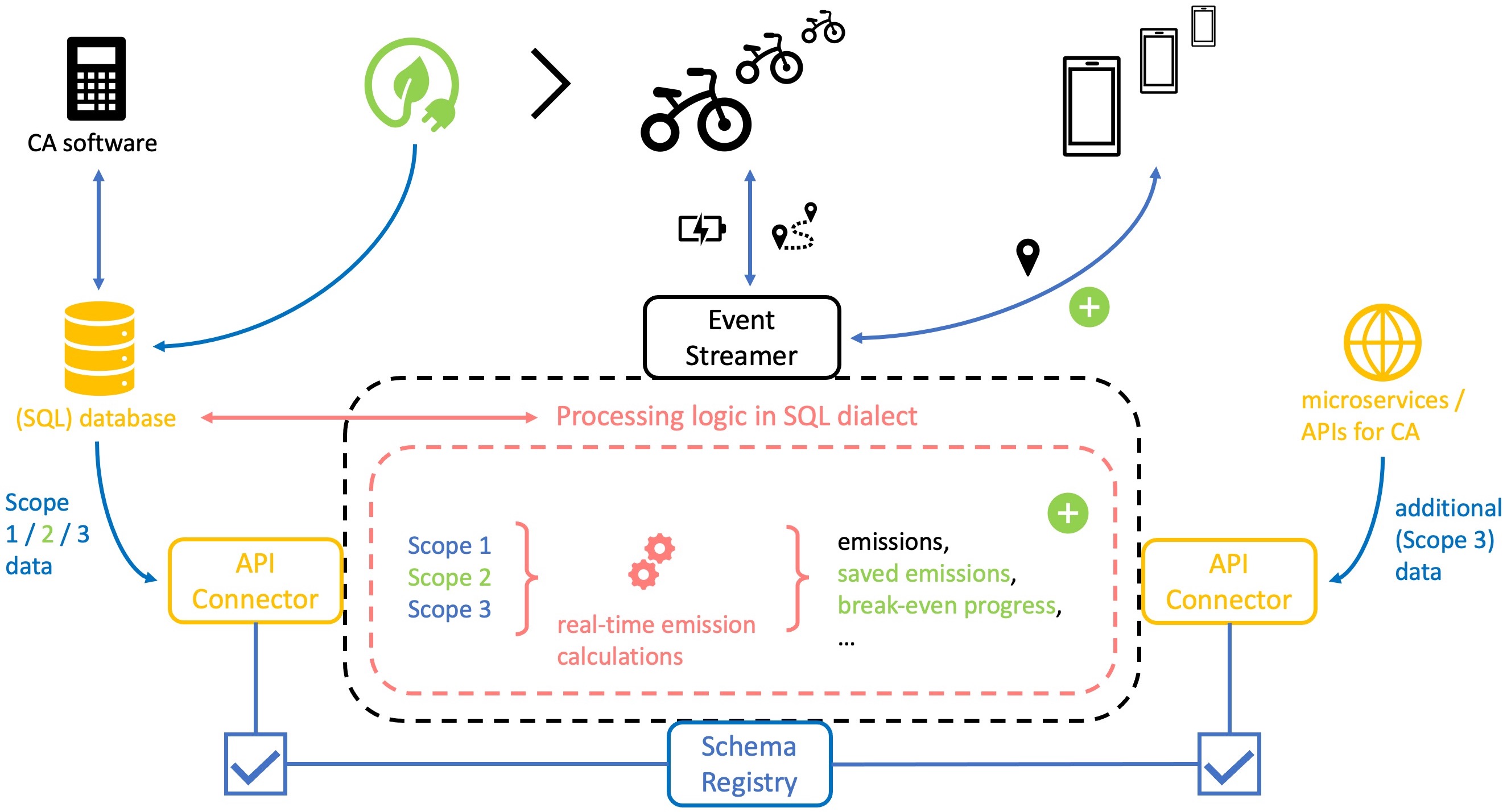

- New opportunities arise for carbon accounting use cases where the principles behind “API connectors”, “schema registers” and “SQL dialects” are used holistically.

Previously in part 1: Input and output level - API adaptability

Part 2: Internal processing logic - Query languages

In part 1, the analogy of a cellular system introduced the concepts of adaptability at the input and output level. We now turn to the inner workings of a system, more specifically the processing logic that describes transformative activities. In a cell, the synthesis of refined components such as proteins from building blocks such as amino acids is a transformative task. This process takes place in structures called ribosomes and requires instructions from mRNA (messenger ribonucleic acid). The language of these instructions is universally applicable between cells and enables replication and adaptation of transformation processes.

IT system design can learn from this example of a ubiquitous language for processing logic. Most interactions with data in storage solutions are performed with query languages. Some of them follow a consistent pattern, but the diversity of solutions has led to a large number of differences. Quite a few IT projects that need to modernize or migrate services suffer from this incompatibility. Technical progress in IT is rapid, and data storage and processing tools are frequently interchanged. Therefore, processing logic defined in a common language and used across many tools has clear advantages. The carbon accounting application domain can also benefit from this approach. Especially because the frequent changes to the input and output layer are usually accompanied by changes to the internal processing logic.

Is there a common language for data processing?

A short and highly simplified answer would be: Yes, it is the Structured Query Language (SQL). Since the advent of relational database management systems (RDBMS) in the 1970s, SQL has been the standard query language for these systems. It even became a de facto standard in 1986 through the authority of the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). ANSI SQL is still the benchmark for many compatibility requirements today. This is due to the ever-growing group of dialects that have emerged with the introduction of new data management solutions, adapting SQL in their own way. But if there is such a standard, where do compatibility problems come from?

The fact is that RDBMS are no longer the only dominant solution for storing and processing data today. Ongoing digitalization requires new solutions to manage the increasing volume, velocity and variety of data. This development is summed up in one word: Big Data. The need for highly scalable databases that can handle different types of data has led to a new paradigm simply called Not Only SQL (NoSQL). A key difference between many SQL and NoSQL databases is the underlying transaction model (ACID vs. BASE), which determines whether a system is designed for consistency (ACID) or high availability (BASE). While RDBMS work according to the ACID paradigm, most NoSQL systems follow the BASE paradigm. If you are interested in explanations of both paradigms, have a look at this blog post by Kirill B. However, I want to focus on another, more practical difference: Schemas.

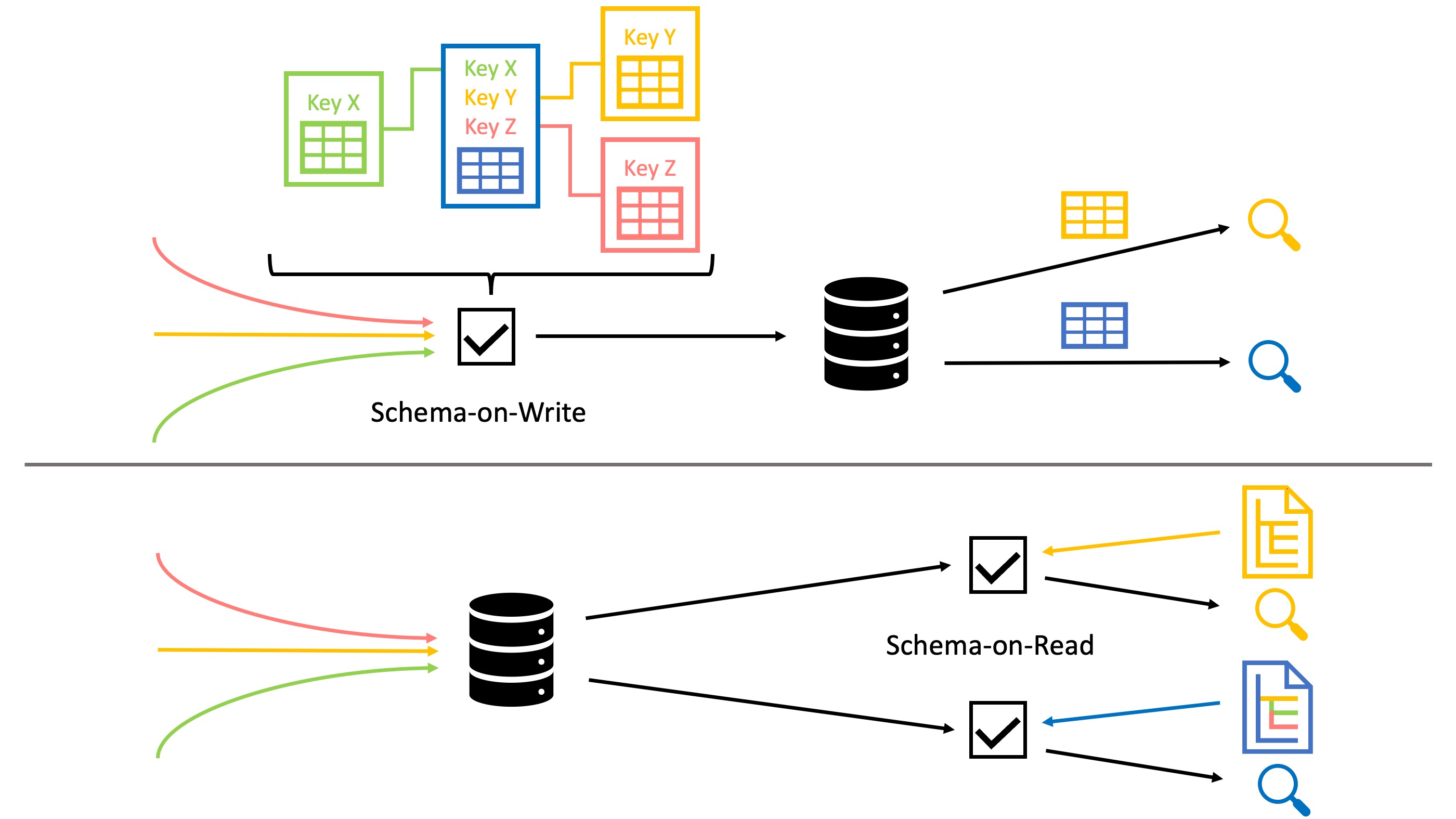

Part 1 introduced schemas as a blueprint for the structure and content of data (models). This concept can also be applied to data in databases. The difference between RDBMS and NoSQL systems is the point of application in data processing. We distinguish between two application scenarios: Schema-on-Write vs. Schema-on-Read. Schema-on-Write, commonly found in RDBMS, suggests that a schema is defined in advance to enforce a standard during data insertion. This is beneficial for data integrity and query optimization, but reduces flexibility when dealing with evolving or unstructured data. The Schema-on-Read approach, commonly found in NoSQL systems, ingests all types of (un)structured data first and defines the requirements during retrieval later. While this allows for a high degree of flexibility in the database itself, most of the work is put in every time a new query is created.

Because of these different approaches, NoSQL databases have developed their own query languages that optimize data processing performance during retrieval. Currently, there is no common standard for such systems, as each new design philosophy for NoSQL has also spawned a new language. This makes it difficult to compare and migrate processing logic not only between SQL and NoSQL, but also between NoSQL systems. However, more and more NoSQL database vendors are realizing the benefits of using an SQL dialect. In most cases, these solutions require a workaround/translation of the existing query language and do not support all SQL operations. However, they reduce the learning curve and help to migrate the existing logic.

Note that the way NoSQL systems work varies widely, as they are tailored to different application requirements. From document stores to graph databases, there are quite a few different solutions that are grouped under the term NoSQL. In the next section, you will find a summary overview of these with the attributes we have discussed.

Adaptable processing logic in practice

Now that we have dived into the issues surrounding the compatibility around query languages, lets look at some practical implications. The choice of a database type is highly context sensitive and is influenced by a lot more factors than the corresponding query language. It makes sense to regularly review the direction in which external and internal developments shift the current use case. Should major changes like an upcoming integration or migration announce themselves, then it pays of to think about the long term effects of using a certain query language.

Transfer of data models and query statements between relational databases using an ANSI-SQL dialect is a safe bet in this regard. But NoSQL databases with their unique language pose the danger of a lock-in effect, resulting in increased cost for licenses and future transitions. What helps to mitigate this risk is to opt for solutions that support open-source standards and protocols. This usually helps to mediate between heterogeneous systems and incentivize innovation. If a NoSQL solution even supports a SQL-like dialect this is preferable as well. Down below you find a table of commonly used NoSQL solutions with information on their query language specifications.

| Database | Transaction Model | Design Type | Query Language | SQL-Like Dialect Supported | SQL Dialect Name (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MongoDB | Mostly BASE | Document Store | MongoDB Query | No | N/A |

| Cassandra | Mostly BASE | Column-Family Store | CQL (Cassandra Query Language) | Partially | N/A |

| Couchbase | ACID for Single-Document Operations, BASE for Multi-Document Operations | Document Store | N1QL (SQL-Like Query Language for JSON) | Yes | SQL++ |

| Neo4j | ACID | Graph Database | Cypher | Yes | Cypher |

| Redis | Mostly BASE | Key-Value Store | Redis Commands | No | N/A |

| Elasticsearch | Mostly BASE | Search Engine | Elasticsearch DSL | Yes | Elasticsearch SQL |

| Amazon DynamoDB | ACID | Key-Value and Document Store | AWS SDKs and APIs | Yes | PartiQL |

Keeping an eye on the adaptability of one database system is a valuable task, but the interaction of multiple storage and processing solutions also deserves close attention. Using common standards and similar query languages favors communication and technology transitions within a company or between partners. But another method can also help increase cross-system adaptability. Instead of managing data exchange between one solution and another, centralized data access layers can be used. Interaction with data from different sources is less dependent on query languages, when intermediate APIs define standardized access. We looked at tools such as API connectors and schema registers that support this strategy in part 1.

To make data exchange even more centralized and efficient, one can use a dedicated system for data collection and distribution. The main requirement for suitable scenarios is often a near real-time exchange of many small data packets. This makes event streaming the first choice for such distribution systems (see previous context post). Popular streaming solutions have addressed the pressing need for efficient adaptation and provide services for simplified API connection and schema management. But distribution is not the only purpose of these systems. Since they also provide processing capabilities for data in transit, the question of a common query language arises again. However, with the most common solutions, we are lucky in this regard. Many use an SQL dialect for data manipulation, which definitely supports the adaptability of centralized data processing. The following table gives an overview of common event streaming solutions in this respect.

| Event Streaming Service | SQL Dialect Supported | SQL Dialect Name (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|

| ActiveMQ | No | N/A |

| Apache Kafka | Yes | KSQL |

| Apache Spark | Yes | Structured Streaming SQL |

| Apache Flink | Yes | Flink SQL |

| Amazon Kinesis | Yes | Kinesis Data Analytics |

| Azure Event Hubs | Yes | Azure Stream Analytics SQL |

| Confluent Cloud | Yes | KSQL |

| Google Cloud Pub/Sub | Yes | Cloud Dataflow SQL |

| IBM Event Streams | Yes | IBM Streams SQL |

| Kafka Streams | Yes | Kafka Streams DSL |

Holistic use case for all discussed technologies

The growing trend of incorporating carbon accounting (CA) into regular business and social activities requires the adaptation of existing IT systems. Because the topic is linked to so many different industries and sciences, its proper application is not simply covered by a one-size-fits-all solution. Rather, existing CA solutions must be integrated into an entire ecosystem of IT systems and change with the demands of Big Data. An IT strategy that pays attention to flexibility in API design and data processing is more likely to accomplish this task. We’ve looked at some methods and tools that can be of great use to this strategy. Let’s illustrate this with a fictitious but plausible carbon accounting use case.

Real-time carbon accounting for an e-bike rental service

A company engages in servitization when it no longer just sells products but bundles them with services to create a new offering. This not only has a positive impact on overall profits, but also creates the opportunity for environmentally friendly business models. Imagine a large bicycle retailer introduces a new decentralized rental service for e-bikes. In doing so, it opens up a whole new market for zero-emission transportation services and reduces downtime for e-bike capacity. Charging the batteries with electricity from renewable sources not only improves the company’s ESG rating, but also allows it to sell a very marketable environmentally friendly service. For carbon accounting of its existing business, the company uses licensed CA software. However, as the company now plans to build a highly dynamic service architecture, this is no longer sufficient.

The business model requires real-time tracking of e-bikes, so that customers can find their vehicle at any time and are charged according to the distance traveled. An event-driven architecture with a streaming service at its core enables this. Since electricity consumption for each trip is linked to the company’s Scope 2 emissions, parts of the carbon accounting can now be calculated in real-time. Relevant metadata such as Scope 3 emissions from upstream supply chain activities can also be integrated via direct API communication. Coupling and decoupling from external services is greatly simplified through plug-and-play API connectors. In addition, a schema registry helps with schema management and validation to protect data integrity and quickly adapt the internal message model to new requirements.

Fundamental data processing that generates source data for the existing carbon accounting software was previously performed in an SQL database. Now, CA calculations can be performed with real-time data in the event streamer, which supports an SQL-like dialect. This facilitates the migration of existing processing logic and makes it adaptable for future transitions. Since Scope 1 and 2 data come from the existing CA solution, Scope 2 deviations are tracked in real-time, and Scope 3 data can be easily obtained from external services, new opportunities arise. The positive contribution of the new rental service to the company’s emissions impact can be broken down for each use of the service. If the customer chooses a renewably charged e-bike instead of a conventionally charged one, the reduction in Scope 2 emissions can be calculated for each ride. This reduction could be achieved through the purchase of renewable energy credits (REC) or on-site renewable energy generation.

Such detailed real-time calculations can be interesting not only for the company’s auditors and analysts. Showing the positive impact on emissions reduction after each rental increases customer satisfaction. One could even incentivize product maintenance and value understanding, by showing how much the savings from each trip contribute to offsetting the emissions from vehicle production. I must emphasize, however, that such calculations would only represent a portion of the company’s overall emissions calculation and should therefore be handled with care. Emissions calculations can quickly be distorted by selective approaches and always require strict control to comply with local regulations.

Despite the highly simplified scenario, we succeeded in capturing the interplay and complementarity of all discussed components for an adaptive IT strategy. This underscores the benefits of these technologies for highly dynamic use cases like carbon accounting. If you’d like to see the bike rental use case in action, I’ve created a tutorial that simulates the scenario. There you can learn about common tools for API management, data processing, and obtaining real-time emissions data. And as an outlook: In upcoming posts on serverless computing, I plan to extend the use case of real-time computation for carbon accounting in a different direction.

Tutorial: How to process diverse data for real-time carbon accounting