Summary part 1:

- The increase in environmental reporting under constantly changing conditions requires adaptable IT systems.

- System interfaces that are subject to external changes can benefit from plug-and-play “API connectors” that follow a strategy of reusability.

- Consistency and validation of data exchange is supported by centralized “schema registers” that follow a strategy of standardization and collaboration.

Adaptation of IT systems to change

We are currently experiencing a time when many different and rapid changes are affecting our daily lives. As digital interaction has become an integral part of our lives, it must also adapt to these changes. In the previous context post, we learned how IT systems can use event streaming to improve the way they handle fast-moving data, i.e., increase velocity. In this post, we look at how systems can handle a large number of changes in data requirements, i.e., how they deal with variety.

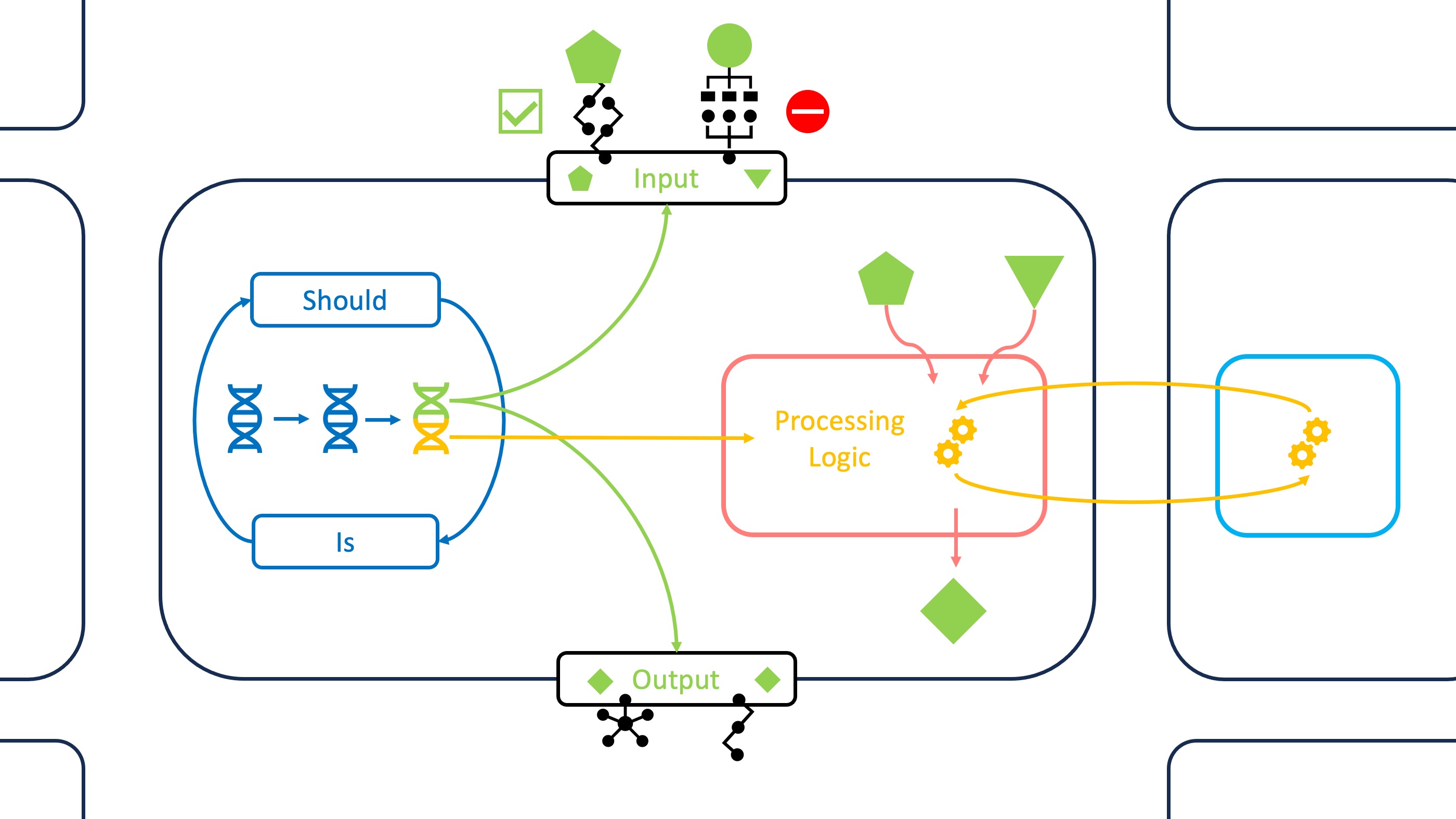

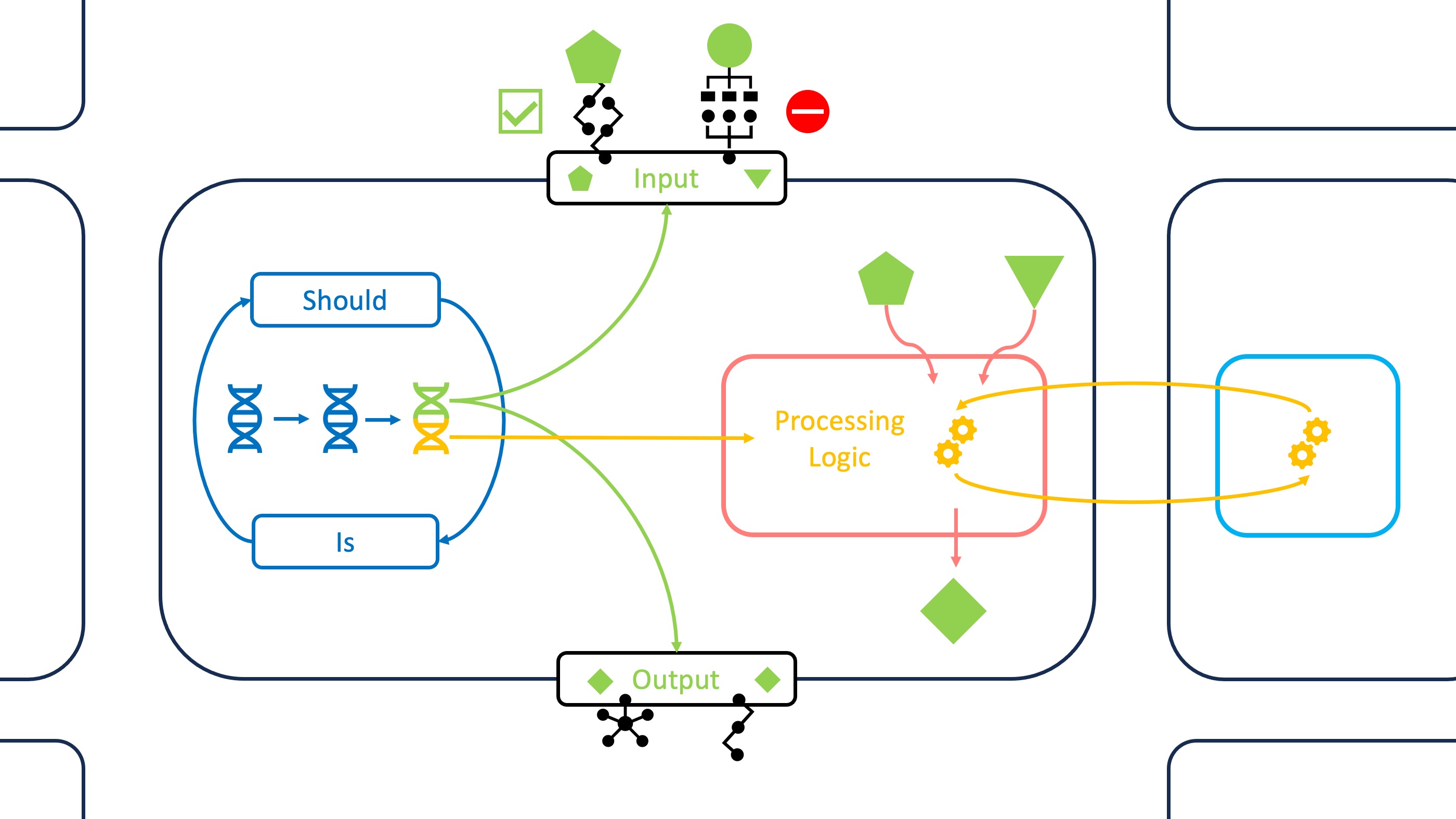

If we consider an IT system as a closed system with environmental influences, there are two aspects that require adaptation. External changes mean that the system must adapt its interfaces to receive correct inputs and deliver correct outputs. Internal changes mean that processing capabilities must be adjusted while the main logic remains consistent. Since I see parallels to cellular activities in the field of biology, I will use these analogies to provide a more tangible introduction to the IT problems at hand. Based on this, I have summarized the methods and technologies that guide adaptations to internal/external changes as the “DNA of an adaptive IT strategy”. The cover image schematically represents the key concepts we will explore in the following sections.

Transfer IT adaptability to carbon accounting

A major external change facing our society and businesses is climate change. Through legislation set by policymakers and self-imposed standards, we are adapting our processes and technologies to reduce the extent of its harmful effects. You may have heard that environmental, social and governance (ESG) frameworks are becoming increasingly important across all industries. An important component of environmental impact reporting is carbon accounting (CA). This involves techniques for measuring, calculating and reporting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

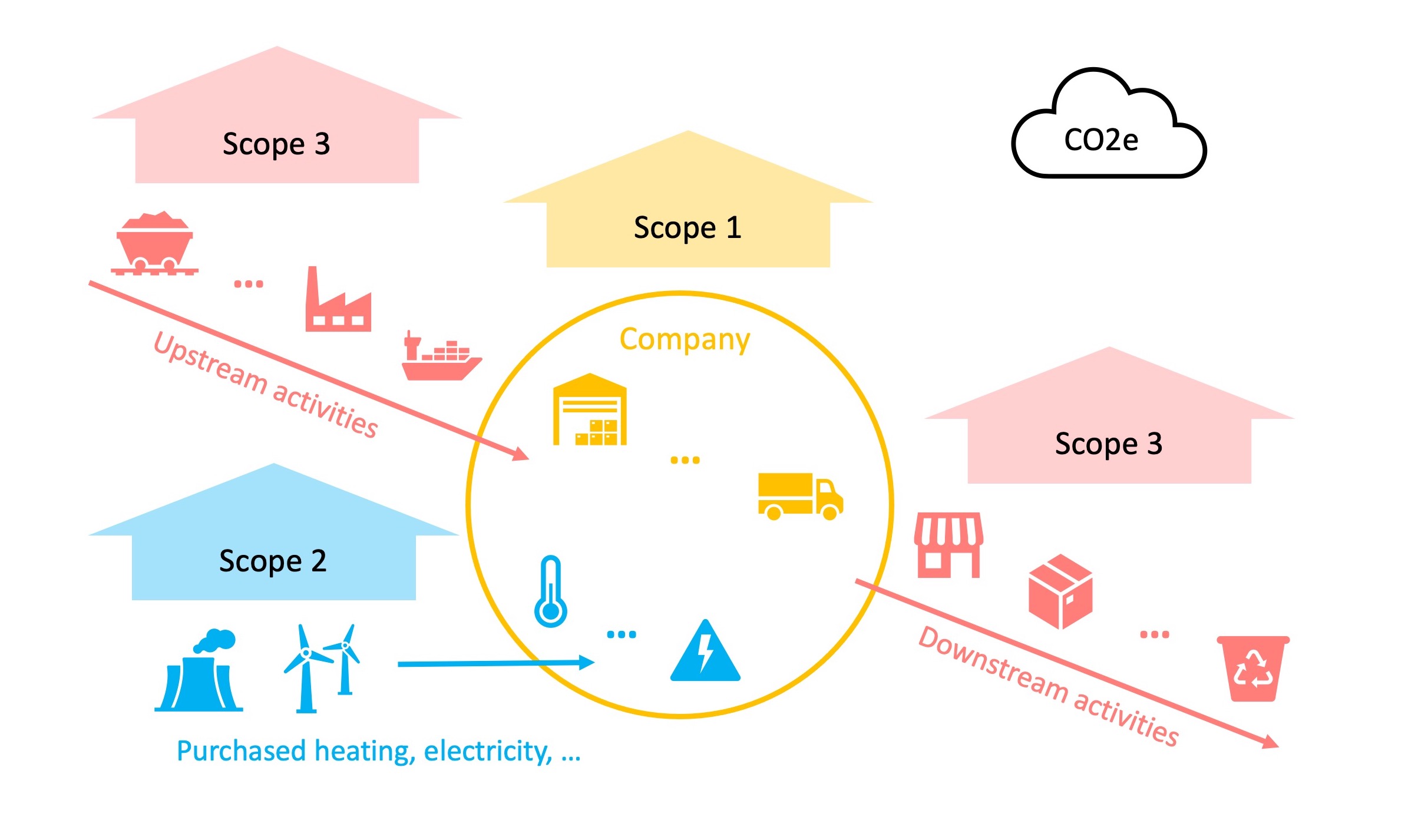

To summarize the climate impact of different greenhouse gas compositions, CA usually works with carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) as a uniform unit of measurement. Another important aspect of carbon accounting is the classification of emissions into three scopes according to their origin. Scope 1 emissions are emitted directly by the reporting company through activities such as facility management and transportation. Scope 2 deals with indirect emissions resulting from the generation of purchased and consumed energy such as electricity and heat. Finally, Scope 3 emissions summarize a variety of indirect factors that relate to the entire supply chain. Examples include emissions related to the production of raw materials and the sales process of a final product. You can educate yourself further with material from the recognized GHG Protocol.

Given the enormous interconnections and interdependencies between companies and their supply chain, you can imagine how difficult it is to correctly measure and calculate Scope 3 emissions. While there is a growing range of carbon accounting software available, these solutions still struggle to deal with the sheer variety of data sources. And this challenge is permanent, because constant adjustments in the supply chain also require constant adjustments in the connected IT systems. For this reason, the IT infrastructure that provides data for CA software is usually highly customized and often needs to be adapted. So we have an excellent use case to explore how IT systems can benefit from the following technologies. In part 1 we take a look at the input and output level. You can find part 2 and the presentation of a carbon accounting use case here.

Part 1: Input and output level - API adaptability

To return to the example of a cellular system: The Interfaces to an external medium are controlled by receptors. These structures have connection points to which only certain messenger substances can dock. A successful connection usually triggers the selective passage of certain molecules. In IT systems, we have application programming interfaces (API) that perform a similar task in exchanging data. APIs should be configured so that only approved actors can send exchange requests and that messages have the expected content. And of course, these configurations should be efficiently adaptable as actors and message content change over time. Before we look at technologies that can help with these tasks, it’s good to have a little background knowledge about APIs.

Why is there so much talk about APIs and what are they made of?

Protocols and data formats that govern the interaction between IT systems have been around since the early days of digital communication. However, their importance has increased in recent history as the Internet has significantly increased the scope and diversity of actors. This has gone so far that APIs are no longer just a tool to enable background communication. The provision of APIs as a means to access services has created a whole new market. Online payments and identity verification, in particular, are leading the way in this regard. Companies like Stripe have achieved billions of dollars in valuation through their API-first strategy.

Meanwhile, there are also services that allow companies to access GHG data and carbon accounting services through APIs. Climatiq is an example of a well-known carbon footprint calculator that we will look at in the associated hands-on tutorial. Regardless of the use case, however, the question remains: What is the current technical standard when it comes to the protocols and data formats behind APIs?

When it comes to communication on the Internet, there is no getting around the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). When using HTTP, two actors follow a request-response model with request methods such as GET to receive data and POST to send data. The addresses to which these requests go follow the commonly used Uniform Resource Locator (URL) standard and are called endpoints. Specialized protocols such as Simple Object Access Protocol (SOAP) are also used by APIs, but most of them (SOAP included) use HTTP methods in a web-based context. SOAP APIs are the preferred choice for use cases where data exchange is subject to strict standards and reliability requirements. However, the most widely used API type follows the Representational State Transfer (REST) guidelines. REST APIs are known for their ease of use and are widely adopted by all types of web applications.

Another decision that must be made during API design is the choice of the data format in which information will be exchanged. The format defines a kind of language that gives structure to data and makes it readable by both machines and humans. It encapsulates the information in a standard that is compatible with different systems. We will look at the two most commonly used formats today. Below you can compare examples from both.

JSON

{

"carbonReport": {

"reportId": "CR12345",

"reportYear": 2022,

"organization": "Green Energy Inc.",

"emissionsData": {

"scope1": {

"directEmissions": 12000

},

"scope2": {

"indirectEmissions": 6200

}

},

"carbonOffsetCredits": [

{

"type": "Renewable Energy Projects",

"quantity": 7500

},

{

"type": "Reforestation",

"quantity": 2800

}

]

}

}

XML

<carbonReport>

<reportId>CR12345</reportId>

<reportYear>2022</reportYear>

<organization>Green Energy Inc.</organization>

<emissionsData>

<scope1>

<directEmissions>12000</directEmissions>

</scope1>

<scope2>

<indirectEmissions>6200</indirectEmissions>

</scope2>

</emissionsData>

<carbonOffsetCredits>

<credit>

<type>Renewable Energy</type>

<quantity>7500</quantity>

</credit>

<credit>

<type>Reforestation</type>

<quantity>2800</quantity>

</credit>

</carbonOffsetCredits>

</carbonReport>

The eXtensible Markup Language (XML) was the first predominant format in the early days of the Internet. It was specifically designed to represent all types of structured documents on the Internet. Main features are the use of hierarchical tags to enclose data elements (e.g. <tag> value </tag>) and many possibilities to extend/customize the format for your own use case.

In the mid-2000s the JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) came up to provide a more light-weight format for web-based APIs. XML requires the application of a parser, a program which extracts information from the tree-like structure and maps it to a local object/data model. JSON on the other hand turned an existing object model from the web-focused programming language Javascript into a data format itself. Its simple structure with "key":value pairs in a hierarchical collection of objects ({}) and arrays ([]), quickly became popular. Nowadays JSON is used extensively in the web context, while XML remains relevant in domains with complex data structures and legacy systems.

How can I adapt APIs to changing communication partners?

Agreements on the technical standard to be used for data exchange are quickly reached, while API maintenance is not an easy task in the face of external changes. We will consider separately the two related problems of changing actors and changing message content. Remember the cell receptors and the selective permeability of a cell membrane? Let’s first focus on the receptors’ abilities to deal with different substances/actors and translate them into technical terms.

Although most web-based APIs today follow REST guidelines, setting up communications is still not simply plug-and-play. There are many variables that need to be adjusted behind the scenes, such as authentication and encryption. Establishing a connection can be especially difficult when proprietary services enforce their own standard. The resulting need for plug-and-play solutions has led to another subset of API software, called API connectors. Simply put, API connectors are adapters that enable seamless integration of data sources and sinks.

They are typically provided as an additional service by platform providers. Popularity and usage have increased, especially since the explosion of cloud services has created a wide range of options for combining software components. This heterogeneity has even spawned solutions that focus solely on enabling simplified and automated connectivity between services. Zapier is such an automation platform that enables all types of integrations, from large cloud services to independent APIs. All in all, it can be helpful to think of connectors as a shortcut in API design. But keep in mind that they can add another dependency and cost factor to your software stack. And while connectors can help harmonize standards, there’s another problem that most of them can’t solve on their own.

How can I adapt APIs to changing message content?

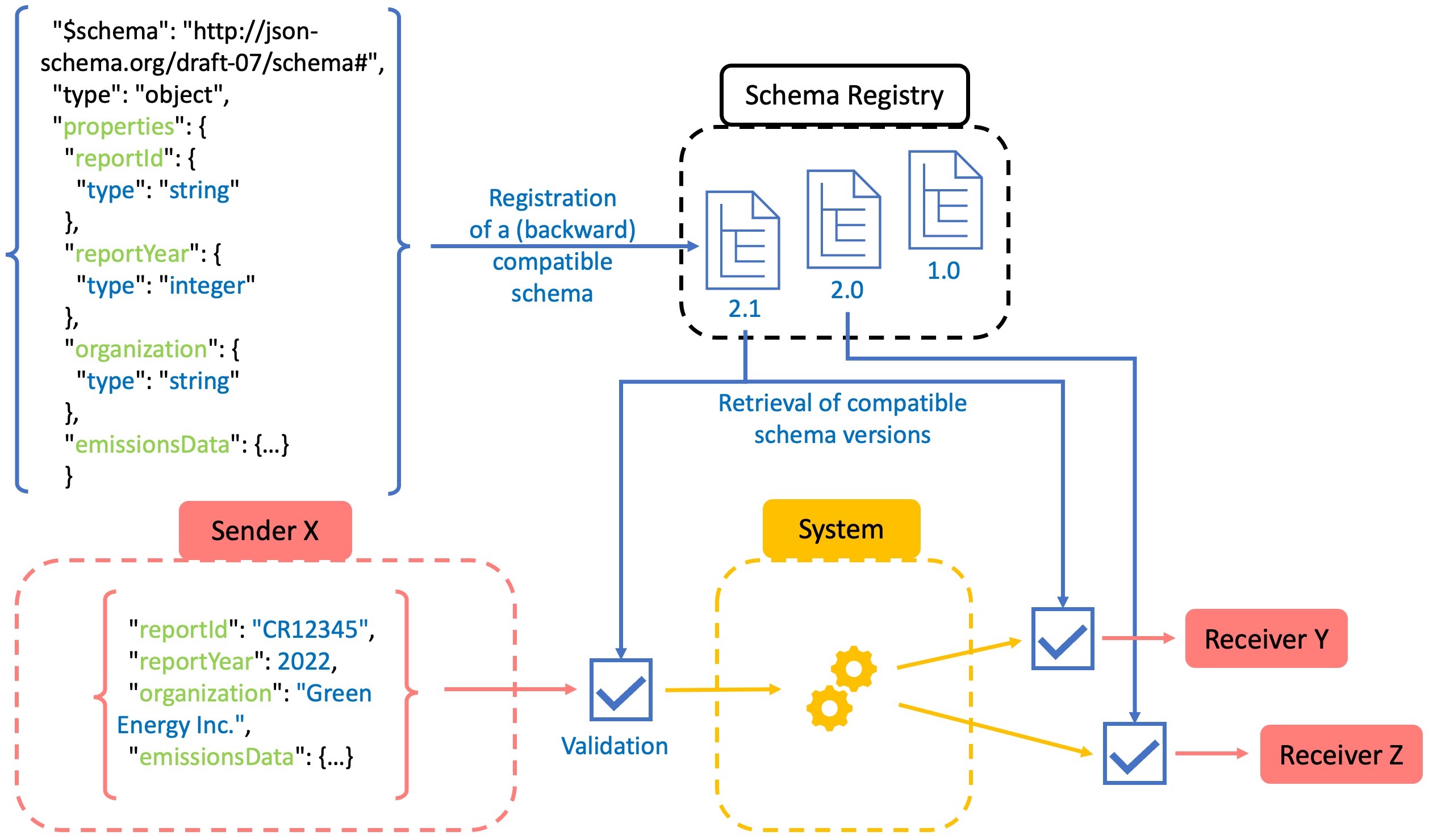

The second dimension to consider in API adaptability concerns the structure and elements of message content. Like a cell membrane that becomes selectively permeable when a receptor is activated, only certain types of content should be allowed through. The previous section introduced data formats and their use to represent a data model in a message. So the obvious idea is to restrict the message content by specifying how the data should be represented in a format like JSON or XML. This task is performed by schemas. Schemas generally define a blueprint for data (models) by specifying rules for structure, names, data types, and more. Thus, for data formats such as JSON and XML, we use JSON Schema and XML Schema Definition (XSD) for this purpose. The instructions are written in JSON or XML itself, which makes the process more user-friendly.

Schemas are great for providing data blueprints, but how do you manage a whole collection of schemas for different communication partners? And how do you deal with change requests from one partner while others still want to use the old schema? For these questions, there are schema management solutions called schema registers. Like repositories, they help you collaborate with others on versions of your shared content (in this case, schemas). They ensure that only authorized changes are made and that backward compatibility is maintained with each new version.

Systems that have many API connections and share event-driven data are prime candidates for using schema registers. As a result, the providers of readily available cloud implementations come from these use cases. Well-known schema registry services include the Confluent Schema Registry for Apache Kafka and the AWS Schema Registry for Amazon EventBridge.

With the above components, the adaptability of APIs becomes easier to handle. Standards and connectors help in onboarding new communication partners. Both communication sides can agree on message content using a schema registry, and the required schema versions are used by APIs to validate incoming and outgoing data. If you would like to see what such a setup might look like in the practical context of carbon accounting, have a look at the corresponding Tutorial. There you will also find some more detailed information on schema registers.

API adaptability in practice

A current trend in software architecture is the use of a microservice pattern. This means that smaller services are developed or acquired separately in order to combine them into one large application. Consequently, this distributed approach requires a lot of interactions between components via APIs. Two pros and cons of a microservice strategy are particularly instructive when it comes to potential API customization pitfalls. Let’s look at how we can mitigate them with the tools I’ve presented and summarize the findings from part 1.

1) Modularity vs. Operational Overhead

- Pro: Independent development and maintenance of decoupled services is more adaptable and faster.

- Cons: Each service must be managed on its own, which can lead to a lot of additional workload.

- Solution: Reusability is the key. Once developed, components and processes should be shared and reused. This also applies to API development and configuration - think API connectors.

2) Faster Development vs. Data Consistency

- Pro: Small development teams can work in a more focused manner and in shorter release cycles.

- Cons: Things break quickly when data is inconsistent because independent teams have difficulty coordinating.

- Solution: Collaboration and standardization are key. Regular synchronization, agreements on changes, and enforcement of standards prevent inconsistencies - think schema registers.

Follow up with part 2: Internal processing logic - Query languages